Deconstructing Claude Research: An Engineering Masterclass from Anthropic

Jul 3, 2025 · 1432 words

Recently, the concept of AI Agents has become incredibly hot, but for most people, it remains a "black box." We see cool demos, but we don't know how they operate internally. When trying to build Agent systems, many often miss the mark, leading to underwhelming results.

Just last month, Anthropic released their Claude Research system and generously included a detailed engineering blog and sample prompts. This is essentially like a top-tier kitchen making its secret recipes public.

Next, I will deconstruct the internal principles of Claude Research to learn how a cutting-edge multi-agent system is designed, built, and polished, and "steal" some valuable engineering experience from Anthropic.

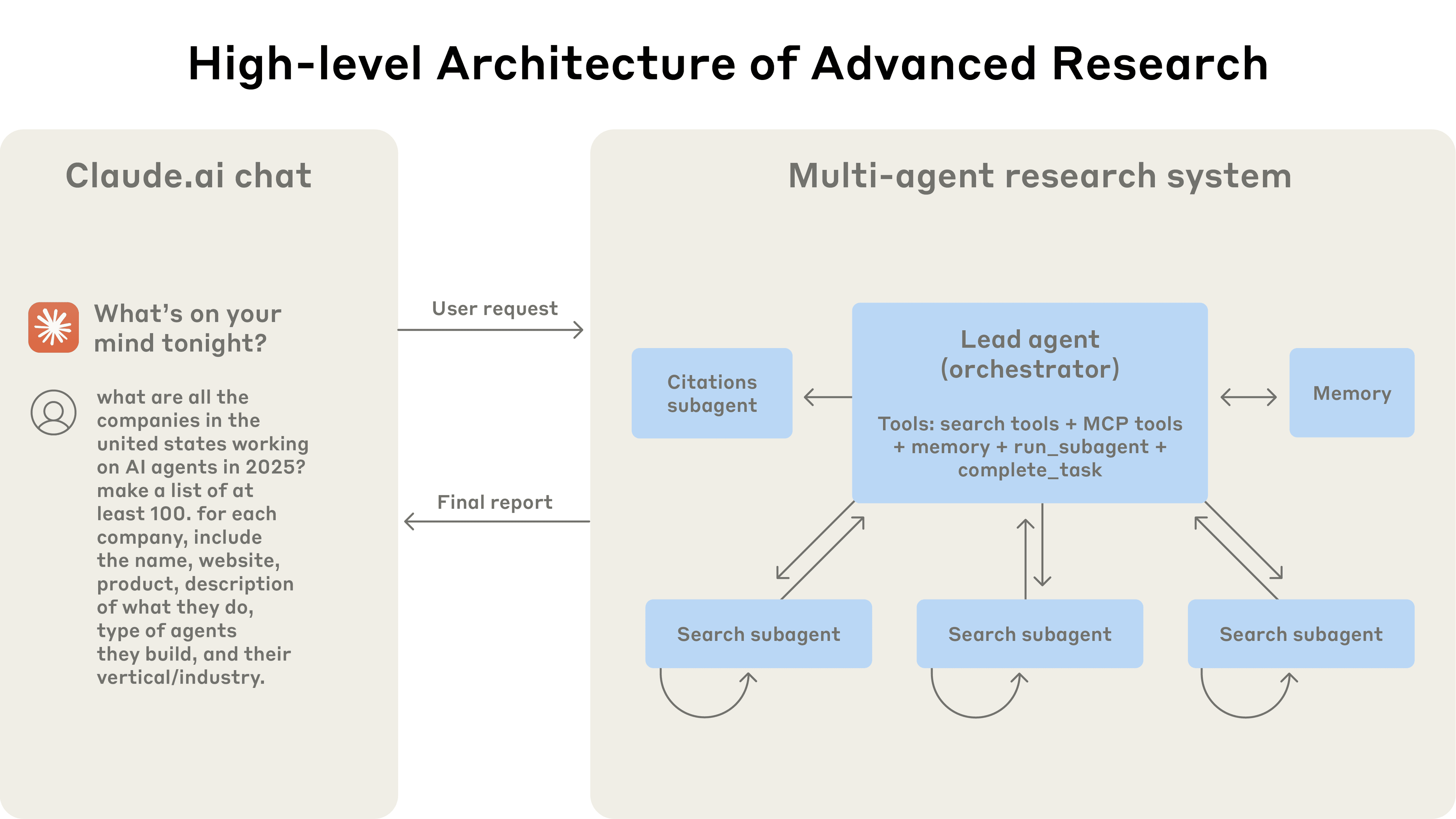

System Architecture and Workflow

Claude Research utilizes a multi-agent architecture following an "orchestrator-worker" pattern. The overall architecture is not overly complex and consists of three core Agent roles:

- Lead Agent: The brain of the entire system. When it receives a complex user request (e.g., "Help me plan a three-month hiking trip"), it is responsible for deep analysis, task decomposition, and creating a detailed research plan.

- Sub-Agent: Once the plan is ready, the Lead Agent creates and launches multiple parallel Sub-Agents. Each Sub-Agent acts as an independent expert responsible for a specific aspect of the plan (e.g., one researches hiking routes, another researches signal coverage along the way). They can work in parallel using tools like search.

- Citation Agent: After all Sub-Agents complete their research and report key information back to the Lead Agent, the Lead Agent synthesizes the information into a complete report. Finally, this "fact-checker" steps in to find and attach accurate source citations for every conclusion in the report.

The entire workflow—receiving the request -> creating a plan -> parallel research -> synthesizing the report -> adding citations—flows seamlessly.

Experimental results show that this multi-agent system performed 90.2% better in internal evaluations than a single, most powerful Claude Opus model. This is somewhat similar to the "emergence" phenomenon in neural networks. When multiple sufficiently intelligent Agent systems work together, they can produce a staggering "1+1 > 2" effect.

Core Engineering Practices

As we can see, the system architecture of Claude Research is not complex, and the collaboration pattern of multi-agent systems is a divide-and-conquer model that many might naturally consider. What is truly worth learning is Anthropic's engineering experience.

1. Prompts Should Be "Collaboration Frameworks," Not Just "Instructions"

Many people dive headfirst into the world of prompting when building Agent systems, as if a perfect prompt will inevitably lead to a successful Agent.

However, Anthropic provided this insight when introducing their system's prompt engineering:

"Think like your agents. Effective prompting relies on developing an accurate mental model of the agent."

"The best prompts for these agents are not just strict instructions, but frameworks for collaboration that define the division of labor, problem-solving approaches, and effort budgets."

The true focus of prompt engineering is not about various detailed tricks, but about giving the Agent clear, specific goals and task workflows.

Especially in multi-agent systems, prompts serve as the framework for collaboration between Agents. They need to define how tasks are divided, the logic for solving problems, and how much effort should be invested in each task. Otherwise, if the boundaries of responsibility are unclear, Sub-Agents will duplicate work or miss key information, leading to task failure.

Anthropic has even open-sourced their prompts. If you have time, I strongly recommend reading through all of them. After doing so, your understanding of prompting will reach a new level.

2. Dynamically Allocate Resources Based on Task Difficulty

Agents themselves are not good at judging whether a problem is a "fly" or a "giant." If you ask it to check the weather, it might launch ten Sub-Agents and create a massive commotion.

Therefore, Claude Research included rules for sub-task scale in its prompts. For simple tasks, only one Sub-Agent is needed, calling 3-10 tools. The most complex research might require 10 Sub-Agents, each using 10-15 tools.

This type of prompt seems simple, but it is actually the most important prompt in the system because LLMs cannot figure this out on their own. In other words, we are defining heuristic rules to inject human wisdom into the Agent system, compensating for the parts where LLMs are weak.

3. Meticulously Design Tools and Their "Manuals"

Providing Agents with the correct and clearly described tools is a key to success. Both the functionality of the tool itself and its descriptive text must be carefully designed. The time and effort invested in tools should be no less than that spent on prompt engineering.

If a tool's description is vague, the Agent might be misled and use the wrong tool (e.g., searching the internet for information that should be found in internal tools). For ReAct systems requiring multi-step execution, a single error can snowball rapidly, leading to incorrect results.

4. Use LLMs to Empower and Evaluate the System

This idea is very clever. Besides letting an LLM be a "player," you can also let it be a "coach" and a "referee."

- As a Coach: When an Agent system fails, another LLM can be used to diagnose the failure logs and analyze which part of the prompt or tool description went wrong, helping us improve.

- As a Referee: It is difficult to evaluate the quality of a research report using code. Anthropic's approach is to let an LLM act as a "judge," scoring the final result from multiple perspectives (such as factual accuracy, citation quality, and comprehensiveness) based on a rubric.

Challenges in System Implementation

Anthropic also detailed the various system implementation challenges they faced while building this Agent in their blog. This part convinced me of the article's value. Anyone attempting to build a complex Agent system must face the following real-world challenges:

- High Latency: This system is inherently slow. A single user request might trigger dozens of model calls between the Lead Agent and Sub-Agents. These calls are interconnected, resulting in long response times that are difficult to meet for real-time interaction needs.

- High Cost: There is no such thing as a free lunch. Dozens of model calls directly lead to high operational costs. The overhead of processing a complex query is far beyond that of a single chat.

- Reliability & Debugging Difficulty: This is a complex distributed system. A small mistake by any Sub-Agent can cause the entire task chain to fail. Even worse, due to the non-deterministic nature of large models, tracking and reproducing a bug is extremely difficult.

- Observability Requirements: Precisely because the system is so complex and fragile, powerful monitoring and visualization tools must be established to track every Agent's behavior, thought process, and tool calls. Without this "observability," the entire system remains a "black box" that is hard to understand and fix.

Summary and Reflections

After organizing these architectural designs, engineering experiences, and real-world challenges, a clear picture emerges.

An AI Agent is definitely not as simple as writing a prompt. A successful AI Agent system is a combination of human-machine intelligence and systems engineering. It requires us to master both the art of communicating cleverly with models and the engineering experience to handle the problems of distributed systems.

Single prompt tricks or pure backend development alone cannot support such a complex system. If these tasks are split among different roles—for example, having a product manager write prompts, a developer build the framework, and an algorithm engineer build benchmarks—the result is likely to be disastrous. Since no one understands the full picture, the end result is a barely functional system cobbled together.

The more critical issue is that a true Agent system cannot be built in one go; it requires a continuous "build-test-analyze-improve" cycle, observing LLM behavior, carefully adjusting prompts, and constructing heuristic rules to make everything work together perfectly. The communication costs brought by splitting roles would make every step of this cycle incredibly inefficient.

I believe the people who can truly build great Agent systems are "Full-stack Agent Engineers" who can bridge all components of the entire chain. They can design the collaboration framework for Agents, write tools, and build robust systems. They can maximize the iteration speed of the Agent system, allowing the Agent to move from the demo stage to a refined, usable system.

In the wave of AI, the more powerful the tools, the more prominent the value of the person at the helm. Mastering this comprehensive, end-to-end capability should be the pursuit of our generation of AI practitioners.