SQLAlchemy Architecture Notes

Jul 12, 2016 · 5415 words

This note primarily aims to help readers better understand SQLAlchemy's architecture. Although the original text comprehensively covers most aspects of SQLAlchemy's architecture, its main purpose is to introduce the architecture, and many parts are not explained in detail. This note serves to provide supplementary explanations. This note consists of 10 sections, which correspond exactly to the 10 sections in the original text, allowing readers to refer to the original text at any time while reading this note.

SQLAlchemy's code is relatively difficult to read, which is determined by its inherent characteristics. Firstly, SQLAlchemy is not an application software but a Python Library. As a database tool, SQLAlchemy must adapt to various mainstream databases, hence it contains a large amount of code dealing with environmental context. Secondly, SQLAlchemy is written in Python, which is a dynamically typed language where variables do not need to be declared, and arbitrary attributes can be added to objects, making code comprehension very challenging. Overall, SQLAlchemy's source code is very difficult to read. Therefore, this note does not contain much analysis of the source code; its focus is on analyzing SQLAlchemy's architectural layers, understanding the design ideas and motivations, and elucidating the patterns used within it.

1. Challenges in Database Abstraction

The original text introduces a concept called the "object-relational impedance mismatch" problem. The meaning of this concept is as follows:

"Object-relational impedance mismatch," sometimes called "paradigm mismatch," refers to the inability of object models and relational models to work well together. Relational database systems represent data in tabular form, while object-oriented languages, such as Java, represent data using interconnected objects. Loading and storing objects using tabular relational databases exposes the following five mismatch issues:

- Granularity: Sometimes, the number of classes in your object model is greater than the number of corresponding tables in the database (we call this the object model having finer granularity than the relational model). Consider an address example to understand this.

- Inheritance: Inheritance is a natural paradigm in object-oriented programming languages; however, relational database systems are fundamentally unable to define similar concepts (some databases do support sub-tables, but that is not standardized at all).

- Equality: Relational database systems define only one concept of "equality": tuples are equal if their primary keys are equal. Object-oriented languages often have two types of equality. For example, in Python,

a is b(identity) anda == b(equality). - Associations: In object-oriented languages, associations are represented as unidirectional references, while in relational database systems, associations are represented as foreign keys. If you need to define bidirectional associations in Python, you must define the association twice.

- Data Access Method: The way you access data in Python is fundamentally different from how you access data in a relational database. In Python, you access one object from another through a reference. However, this is not an efficient method for data retrieval in a relational database; you might want to minimize the number of SQL queries.

If the system you are developing uses an object-oriented language and a relational database, the object-relational impedance mismatch problem will inevitably arise when the system scales to a certain extent. ORM tools like SQLAlchemy are designed to solve these types of problems.

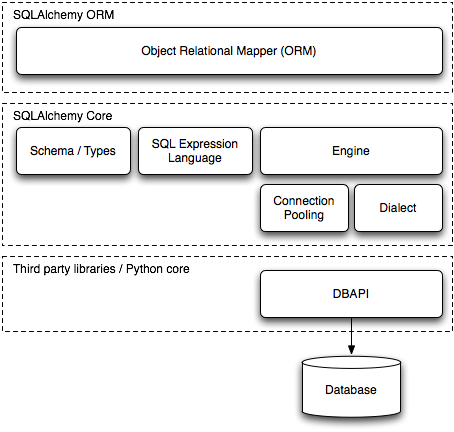

2. SQLAlchemy's Two-Tier Architecture

The original text already provides a diagram illustrating SQLAlchemy's two architectural layers:

SQLAlchemy's two main functionalities are Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) and SQL Expression Language. The SQL Expression Language can be used independently of the ORM. When users employ the ORM, the SQL Expression Language works behind the scenes, but users can also manipulate its behavior through exposed APIs.

Sections 3 to 9 elaborate on the SQLAlchemy architectural layers shown in the diagram above. Specifically, sections 3-5 discuss the Core layer, while sections 6-9 discuss the ORM layer.

As we know, SQL language is broadly categorized into four types:

- DDL (Data Definition Language) - Primarily includes CREATE TABLE, DROP, ALTER, used to define database schemas.

- DML (Data Manipulation Language) - Primarily includes SELECT, used to query data.

- DQL (Data Query Language) - Primarily includes INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, used to insert, update, and delete data.

- DCL (Data Control Language) - Primarily includes GRANT, etc.

We will not focus on DCL for now. Among DDL/DML/DQL, DDL is responsible for defining the database schema, while DML and DQL are responsible for data access. Although they all belong to SQL, they focus on entirely different aspects. SQLAlchemy uses different modules to abstract these two parts. In the Core layer, SQLAlchemy uses Metadata to abstract DDL and the SQL Expression Language to abstract DML and DQL. In the ORM layer, SQLAlchemy uses mapper to abstract DDL and Query objects to abstract DML and DQL. The following sections 4/5/6/7 correspond to these four areas respectively:

- (4) Schema Definition - Core layer schema definition (DDL)

- (5) SQL Expression Language - Core layer data access (DML/DQL)

- (6) Object-Relational Mapping - ORM layer schema definition (DDL)

- (7) Querying and Loading - ORM layer data access (DML/DQL)

Readers may find many connections and similarities by comparing the content of Section 4 with Section 6, and Section 5 with Section 7.

3. Improved DBAPI

First, we need to understand what DBAPI is. The following content is quoted from the SQLAlchemy documentation glossary:

DBAPI is an abbreviation for "Python Database API Specification." This is a widely used specification in Python that defines the usage pattern for third-party libraries connecting to databases. DBAPI is a low-level API, essentially at the lowest layer in a Python application, interacting directly with the database. SQLAlchemy's dialect system is built according to DBAPI operations. Essentially, a dialect is DBAPI plus a specific database engine. By providing different database URLs in the

create_engine()function, a dialect can be bound to different database engines.

—— SQLAlchemy Documentation - Glossary - DBAPI

The PEP documentation can be dry; we can intuitively understand the DBAPI usage pattern through this example code:

connection = dbapi.connect(user="root", pw="123456", host="localhost:8000")

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute("select * from user_table where name=?", ("jack",))

print "Columns in result:", [desc[0] for desc in cursor.description]

for row in cursor.fetchall():

print "Row:", row

cursor.close()

connection.close()

In contrast, SQLAlchemy's usage pattern is as follows:

engine = create_engine("postgresql://user:pw@host/dbname")

connection = engine.connect()

result = connection.execute("select * from user_table where name=?", "jack")

print result.fetchall()

connection.close()

As can be seen, the usage patterns of both are very similar, both querying directly using SQL statements. SQLAlchemy only provides encapsulation but does not perform high-level abstraction. However, this is just the simplest way to use SQLAlchemy. Later, we will see that the SQL Expression Language allows for highly abstract descriptions, eliminating the need to write SQL statements manually.

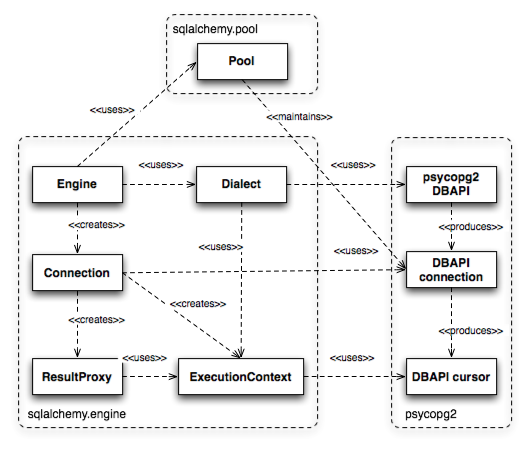

The original text provides a diagram of the core classes in SQLAlchemy's dialect system:

Referring to the description in the original text, let's examine the source code:

The

executemethod of bothEngineandConnectionclasses returns aResultProxy, which provides an interface similar to DBAPI's cursor but with richer functionality.Engine,Connection, andResultProxycorrespond respectively to the DBAPI module, a specific DBAPI connection object, and a specific DBAPI cursor object.At the lower level,

Enginereferences an object calledDialect.Dialectis an abstract class with numerous implementations, each corresponding to a specific DBAPI and database. AConnectioncreated for anEngineconsults theDialectto make choices, and the behavior ofConnectionvaries for different target DBAPIs and databases.When a

Connectionis created, it obtains and maintains a DBAPI connection from a connection pool. This connection pool is calledPooland is also associated with theEngine.Poolis responsible for creating new DBAPI connections and typically maintains a pool of DBAPI connections in memory for frequent reuse.During the execution of a statement,

Connectioncreates an additionalExecutionContextobject. This object exists from the moment execution begins until theResultProxyis destroyed.

Engine and Connection

The global function create_engine is used to create an Engine object. The first argument to this function is a database URL, and there are also keyword arguments to control the characteristics of Engine, Pool, and Dialect objects. The strategy keyword argument is used to specify the strategy when creating the Engine. The function looks up the corresponding strategy (a subclass of EngineStrategy) in the global strategies dictionary and passes its parameters to the strategy class's create method. If the strategy parameter is not provided, the default strategy DefaultEngineStrategy is used. Observing the create method of each EngineStrategy subclass, it is found that they all create Dialect and Pool objects before creating the Engine object, and store references to these two objects within the Engine object, ensuring that the Engine object can handle DBAPI through Dialect and Pool.

The Connection class appears to be more powerful than the Engine class. The Engine.connect() method is used to create a Connection:

_connection_cls = Connection

def connect(self, **kwargs):

return self._connection_cls(self, **kwargs)

Calling Engine.connect() actually passes the Engine object itself as the first argument to the Connection constructor, but the Connection constructor also needs to call the Engine.raw_connection() method to obtain a database connection. This is primarily to facilitate Engine's implicit execution interface. When a Connection has not been created, the Engine can also call raw_connection() itself to obtain a database connection.

Regardless, Connection holds a reference to Engine and can access Pool and Dialect objects through Engine. Database operations are typically performed using the Connection.execute() method.

Pool

Pool is responsible for managing DBAPI connections. When a Connection object is created, it retrieves a DBAPI connection from the connection pool, and when the close method is called, the connection is returned to the pool.

The code for Pool is defined in pool.py and includes the abstract parent class Pool, along and several subclasses with specific functionalities:

QueuePoollimits the number of connections (used by default)SingletonThreadPoolmaintains one connection per threadAssertionPoolallows only one connection at any time, otherwise raises an exceptionNullPoolperforms no pooling operations, directly opens/closes DBAPI connectionsStaticPoolhas only one connection

Executing SQL Statements

The execute method of Connection executes an SQL statement and returns a ResultProxy object. The execute method accepts various types of parameters; the parameter type can be a string or a common subclass of ClauseElement and Executable. The parameters of the execute method will be discussed in detail below; here, we primarily analyze the underlying process when the execute method is executed.

def execute(self, object, *multiparams, **params):

if isinstance(object, util.string_types[0]):

return self._execute_text(object, multiparams, params)

try:

meth = object._execute_on_connection

except AttributeError:

raise exc.InvalidRequestError(

"Unexecutable object type: %s" %

type(object))

else:

return meth(self, multiparams, params)

As can be seen, the execute method checks the type of the SQL statement object. If it's a string, it calls the _execute_text method for execution; otherwise, it calls the object's _execute_on_connection method. The _execute_on_connection method of different objects will call Connection._execute_*() methods, specifically:

- For

sql.FunctionElementobjects,Connection._execute_function()is called. - For

schema.ColumnDefaultobjects,Connection._execute_default()is called. - For

schema.DDLobjects,Connection._execute_ddl()is called. - For

sql.ClauseElementobjects,Connection._execute_clauseelement()is called. - For

sql.Compiledobjects,Connection._execute_compiled()is called.

All the above Connection._execute_*() methods call the Connection._execute_context() method. The first parameter of this method is the Dialect object, and the second parameter is the constructor for the ExecutionContext object (obtained from the Dialect object). Within the method, the constructor is called to create an ExecutionContext object, and based on the context object's state, relevant methods of the dialect object are called to produce results. Different methods of the dialect object are called for different states; generally, Dialect.do_execute*() methods are invoked.

From the process of method calls described above, it can be seen that the Connection's execute method ultimately delegates the task of generating results to the Dialect's do_execute method. SQLAlchemy uses this approach to handle diverse DBAPI implementations: Connection consults the Dialect to make choices when executing SQL statements. Therefore, the behavior of Connection varies for different target DBAPIs and databases.

Dialect

Dialect is defined in the engine/interfaces.py file as an abstract interface, which defines three do_execute*() methods: do_execute(), do_executemany(), and do_execute_no_params(). Subclasses of Dialect define their execution behavior by implementing these interfaces. The default dialect subclass in SQLAlchemy is DefaultDialect. In the default implementation, the do_execute method calls Cursor.execute, where Cursor is a class from DBAPI. This is where the SQLAlchemy Core layer connects with the DBAPI layer.

The sqlalchemy.dialects package contains dialects for databases such as Firebird, MSSQL, MySQL, Oracle, PostgreSQL, SQLite, and Sybase. Taking SQLite as an example, SQLiteDialect inherits from DefaultDialect, and there are SQLiteDialect_pysqlite and SQLiteDialect_pysqlcipher. SQLite's dialect does not override do_execute*(); instead, it overrides other methods to define behaviors different from DefaultDialect. For instance, SQLiteDialect handles the fact that SQLite does not have built-in DATE, TIME, and DATETIME types.

ResultProxy

ResultProxy wraps a DBAPI cursor object, making individual fields within a result row easier to access. In database terminology, a result is often referred to as a row.

A field can be accessed in three ways:

row = fetchone()

col1 = row[0] # Access by positional index

col2 = row['col2'] # Access by name

col3 = row[mytable.c.mycol] # Access by Column object

ResultProxy defines the __iter__ method, allowing for-loops to be used on a ResultProxy object, which has the same effect as repeatedly calling the fetchone method:

def __iter__(self):

while True:

row = self.fetchone()

if row is None:

return

else:

yield row

4. Schema Definition

A database schema is the structure of a database system described in a formal language. In a relational database, the schema defines tables, fields within tables, and the relationships between tables and fields.

—— Webopedia

Intuitively, the following SQL statements describe a database schema:

CREATE TABLE users (

id INTEGER NOT NULL,

name VARCHAR,

fullname VARCHAR,

PRIMARY KEY (id)

);

CREATE TABLE addresses (

id INTEGER NOT NULL,

user_id INTEGER,

email_address VARCHAR NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (id),

FOREIGN KEY(user_id) REFERENCES users (id)

);

SQLAlchemy's schema definition functionality expresses the content of the above SQL statements in an abstract way. The following code defines the same schema as the SQL statements above:

metadata = MetaData()

users = Table('users', metadata,

Column('id', Integer, primary_key=True),

Column('name', String),

Column('fullname', String),

)

addresses = Table('addresses', metadata,

Column('id', Integer, primary_key=True),

Column('user_id', None, ForeignKey('users.id')),

Column('email_address', String, nullable=False),

)

metadata.create_all(engine)

The name MetaData comes from the Metadata Mapping pattern, but the actual implementation of this pattern is found in Table and the mapper() function, which will be discussed in detail in the ORM section below.

A MetaData object stores all schema-related structures, especially Table objects. The sorted_tables method returns a topologically sorted list of Table objects. For more on topological sorting of tables, see Section 9, "Unit of Work."

Examining the source code, the first two parameters of the Table constructor __new__ are the table name and the MetaData object, respectively. The constructor creates a Table object with a unique name; if the constructor is called again with the same table name and MetaData object, it returns the same object. Thus, the Table constructor acts as a "registrar."

5. SQL Expression Language

The Query object implements the Query Object pattern defined by Martin Fowler. Martin Fowler describes this pattern in his book as follows:

SQL is an evolving language, and many developers are not very familiar with it. Furthermore, when writing queries, you need to know what the database schema looks like. The Query Object pattern can solve these problems.

A Query Object is an Interpreter Pattern, meaning an object that can transform itself into an SQL query. You can create a query by using classes and attributes instead of tables and fields. This way, you can write queries without relying on the database schema, and changes to the schema will not have a global impact.

—— Martin Fowler: Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, Query Object

Mike Bayer points out that the creation of SQL expressions primarily uses Python expressions and overloaded operators.

Source Code Analysis

sqlalchemy.sql.dml.Insert is a subclass of UpdateBase, and UpdateBase is simultaneously a subclass of ClauseElement and Executable, so instances of Insert can be passed to Connection.execute().

select is a global function, not a class. In sql/expression.py, public_factory is called to transform the selectable.Select class into the function select, meaning Select.__init__() is assigned to select.

6. Object-Relational Mapping (ORM)

What is ORM? Let's first look at the Data Mapper pattern described by Martin Fowler in his book. The original text mentions that SQLAlchemy's ORM system draws inspiration from this pattern.

Objects and relational databases organize data differently. Many parts of objects, such as inheritance, do not exist in relational databases. When you build an object model with a lot of business logic, the object's schema and the relational database's schema may not match.

However, you still need to convert between the two schemas, and this conversion itself becomes a complex matter. If in-memory objects know the structure of the relational database, a change in one will affect the other.

A Data Mapper is a layer that separates in-memory objects from the database. Its responsibility is to decouple objects and relational databases and to transfer data between them. With a Data Mapper, in-memory objects do not need SQL interface code, nor do they need to know the database schema, or even whether a database exists.

—— Martin Fowler: Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, Data Mapper

To understand the meaning of the above passage, let's look at the following example code:

from sqlalchemy import Table, MetaData, Column, Integer, String, ForeignKey

from sqlalchemy.orm import mapper

metadata = MetaData()

users = Table('users', metadata,

Column('id', Integer, primary_key=True),

Column('name', String),

Column('fullname', String),

)

class User(object):

def __init__(self, name, fullname, password):

self.name = name

self.fullname = fullname

self.password = password

mapper(User, users)

In the code above, the User class is a user-defined class, which is an entity object in the business logic. users is the database schema (which has been analyzed in detail in Section 4, "Schema Definition"). The mapper function is used to map the User class to the schema. Notice that the User class is completely independent of the database schema; this class can be written without knowing the data storage method. This achieves the separation of objects and the database.

Two Types of Mappings

The terms "traditional" and "declarative" merely refer to two styles, old and new, for user-defined ORM in SQLAlchemy. Initially, SQLAlchemy only supported traditional mapping; later, declarative mapping emerged, built upon traditional mapping, offering richer functionality and more concise expression. The two mapping styles can be used interchangeably, yielding identical results. Furthermore, declarative mapping is ultimately converted into traditional mapping—mapping a user-defined class using the mapper() function—thus, there is no essential difference between the two mapping styles.

In my understanding, traditional mapping has a clearer approach and better embodies the idea of separating objects from the database, while declarative mapping is more powerful.

7. Querying and Loading

Query Object

As previously mentioned, SQLAlchemy's ORM layer is built on top of the Core layer; therefore, when using the ORM layer, users will not use interfaces like connection.execute() from the Core layer. Session becomes the sole entry point for users to interact with the database. When users perform queries through Session, they need to use a Query object. The example code is as follows:

session = Session(engine)

result = session.query(User).filter(User.name == 'ed').all()

The Query object implements the Query Object pattern defined by Martin Fowler. As mentioned in Section 5, select() also implements this pattern. In fact, Query and select() have very similar functionalities, both performing database queries, except one operates at the Core layer and the other at the ORM layer. Compare with the select() code:

connection = engine.connect()

result = connection.execute(select([users])).where(users.c.name == 'ed')

The two parts, QUERY TIME and LOAD TIME, exist because the ORM layer operates above the Core layer (SQL Expression Language) and needs to invoke the infrastructure of the SQL Expression Language to function.

8. Session

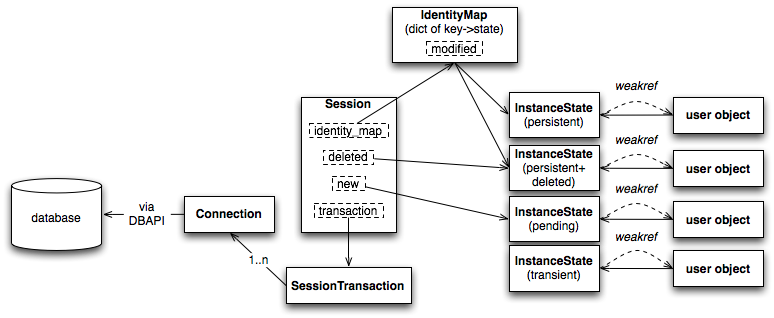

Figure 20.13 in the original text clearly illustrates the components of a session:

The previous section analyzed the Query object, which is primarily responsible for querying and object loading. The Session, on the other hand, handles more detailed and intricate tasks. As shown in the diagram, a Session object comprises three important parts:

- Identity Map

- Object State

- Transactions

The collaboration between the Identity Map and state tracking is, in my opinion, one of the two most ingenious aspects of SQLAlchemy's design. These two parts will be introduced in detail below.

Identity Map

Identity Map is a pattern defined by Martin Fowler. Below is Martin Fowler's introduction to this pattern in his book:

An old proverb says that a person with two watches never knows what time it is. When loading objects from a database, if two watches (two objects) are inconsistent, you'll have even greater trouble. You might inadvertently load data from the same database and store it into two different objects. When you update both objects simultaneously, you'll get strange results when writing the changes to the database.

This is also related to an obvious performance issue. If you load the same data more than once, it will lead to expensive remote call overhead. Therefore, avoiding loading the same data twice not only ensures correctness but also improves application performance.

An Identity Map keeps a record of all the objects that have been read from the database in a single transaction. When you need a piece of data (loaded into an object), you first check the Identity Map to see if it's already there.

—— Martin Fowler, Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, Identity Map

Simply put, an Identity Map is a Python dictionary that maps from a Python object to its database ID. When an application attempts to retrieve an object, if the object has not yet been loaded, the Identity Map loads it and stores it in the dictionary; if the object has already been loaded, the Identity Map retrieves the existing object from the dictionary. The Identity Map offers two significant benefits:

- Loaded objects are "cached," eliminating the need for multiple loads and avoiding extra overhead. This is essentially a form of lazy loading.

- It ensures that the application retrieves a unique object, preventing data inconsistency issues.

In SQLAlchemy's actual implementation, the key of IdentityMap is the database ID, but the value is not an object itself, but an InstanceState that stores the object's state. The "State Tracking" section below explains why IdentityMap is designed this way.

State Tracking

Within a Session, an object has four states, recorded by an InstanceState:

- Transient - This object is not in the session and has not been saved to the database. That is, it does not have a database ID. The only relationship this object has with the ORM is that its class is associated with a

mapper(). - Pending - When you call

add()and pass a transient object, it becomes pending. At this point, it has not yet been flushed to the database, but it will be saved to the database after the next flush. - Persistent - An object that is within the session and has a record in the database. There are two ways to obtain a persistent object: one is by flushing a pending object to make it persistent, and the other is by querying the object from the database.

- Detached - An object that corresponds (or once corresponded) to a record in the database but is no longer in any session. After a transaction in the session is committed, all objects become detached.

An object's journey from entering a Session to leaving a Session involves traversing these four states sequentially (for newly created objects, all four states are traversed; other objects do not have a transient state). First, it enters the Session, its in-memory data changes, and it enters the pending state; then, through a flush operation, the in-memory changes are saved to the database, entering the persistent state; finally, it leaves the Session, entering the detached state.

After understanding the distinctions between these four states, we can see that the Session primarily tracks objects in the pending state, because the in-memory data of these objects is inconsistent with the database. Once an object reaches the persistent state, it actually no longer needs to be tracked, as its in-memory data is now consistent with the database, and the Session can discard these objects at any subsequent point in time.

So, when should this object be discarded? Firstly, it cannot be discarded too early. Because when an object is in the persistent state, a user might perform a query operation and find this in-memory object via the identity map. If discarded too early, the object would have to be reloaded from the database, causing unnecessary overhead. Secondly, it cannot be discarded too late, as this would retain a large number of objects in the session, preventing timely memory reclamation. The best approach, then, is to let the garbage collector decide. The garbage collector will release objects and reclaim memory when memory is insufficient, while also allowing objects to remain in memory for a period, making them available when needed.

The Session uses a weak reference mechanism to achieve this. A weak reference means that an object may still be garbage collected even if references to it are held. When an object is accessed via a reference at a certain moment, the object may or may not exist; if it does not exist, the object is reloaded from the database. If it's desired that an object not be collected, one simply needs to maintain another strong reference to it. The IdentityMap in Session is actually a "weak value dictionary," meaning that the values in the map are weakly referenced, and when there are no strong references pointing to a value in the dictionary, that key-value pair will be removed from the dictionary. For detailed information on weak value dictionaries, refer to the Python official documentation - WeakValueDictionary.

The diagram shows that the Session object contains a new attribute and a deleted attribute. Reading the source code reveals that Session also contains a dirty attribute. All three of these attributes are collections of objects. As the names suggest, new refers to objects just added to the session, dirty refers to objects just modified, and deleted refers to objects marked for deletion within the session. These three types of objects share a common characteristic: they are all data in memory that has been changed and is inconsistent with the database, precisely the pending state among the "four states of an object" mentioned above. This means that the Session holds strong references to all objects in the pending state, ensuring they are not garbage collected. For other objects, the Session only retains weak references.

9. Unit of Work

Unit of Work is also a pattern defined by Martin Fowler in his book, and SQLAlchemy's unitofwork module implements this pattern. The SQLAlchemy documentation states that the Unit of Work pattern "automatically tracks changes to objects and periodically flushes pending changes to the database" (SQLAlchemy Documentation - Glossary - unit of work). The relationship between Unit of Work and Session is as follows: the Session defines the four states of objects, while the Unit of Work is responsible for transitioning pending objects in the session to the persistent state, completing database persistence work in this process. Users call the Session's commit method to save data queries, updates, and other operations to the database. The original text mentions that the commit method calls the flush method for the "flush" operation, and all actual work of flush is performed by the Unit of Work module.

The Unit of Work is, in my opinion, the second of the two most ingenious parts of SQLAlchemy's design. To understand the ingenuity of the Unit of Work, one must first understand the main difficulties in database persistence. Memory is very fast, and the state of many objects can change within a short period. To persist these changes, the simplest approach is to generate an SQL statement (possibly an INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE statement) for each changed object and perform a database call. However, database write speeds are much slower than memory, and too many database operations will severely degrade performance. To achieve efficiency, a batch of data needs to be sent to the database at once.

However, these objects cannot be persisted in an arbitrary order. For example, when a foreign key relationship exists between two tables, if an object with a foreign key needs to be persisted, the object referenced by the foreign key must be persisted first. This means that although a batch of objects can be persisted at once, when an object with a foreign key is encountered, the process must pause to persist the foreign-key-referenced object first. Thus, many database calls are still made in practice.

The Unit of Work, however, uses a superior pattern: before performing persistence operations, it first arranges the order in which objects are to be persisted. During persistence, batches of objects are simply sent to the database without needing to consider other dependencies before processing each object. The Unit of Work models the dependencies between objects using a directed graph, and based on the topological sort of a directed acyclic graph in graph theory, the flush order for all objects can be arranged. The specific steps are clearly explained in the original text and will not be reiterated here.

10. Conclusion

Before researching SQLAlchemy, I had never heard of the ORM concept, nor was I aware of famous ORM tools like Hibernate. Last year, while doing web development with JSP, I encountered the problem of converting between relational databases and objects, and realized this was a necessary yet complex task. Using an ORM tool in development would undoubtedly greatly enhance program robustness. Relational databases are an indispensable technology, and object-oriented languages have always been mainstream. ORM combines these two. SQLAlchemy is the most popular ORM tool in Python and is the de facto standard. In fact, Python's famous web framework Django has often been criticized for having its own ORM system and not supporting SQLAlchemy. If you have never heard of the ORM concept, I recommend you learn about SQLAlchemy and try using this library in your development.

References

- SQLAlchemy 1.0 Official Documentation

- Martin Fowler: Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture

- Mike Bayer: Patterns Implemented by SQLAlchemy

- Mike Bayer: SQLAlchemy Architecture Review

- Catalog of Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture

- Hibernate Documentation - What is ORM